Lucid Dream (in memory of Michael Leunig)

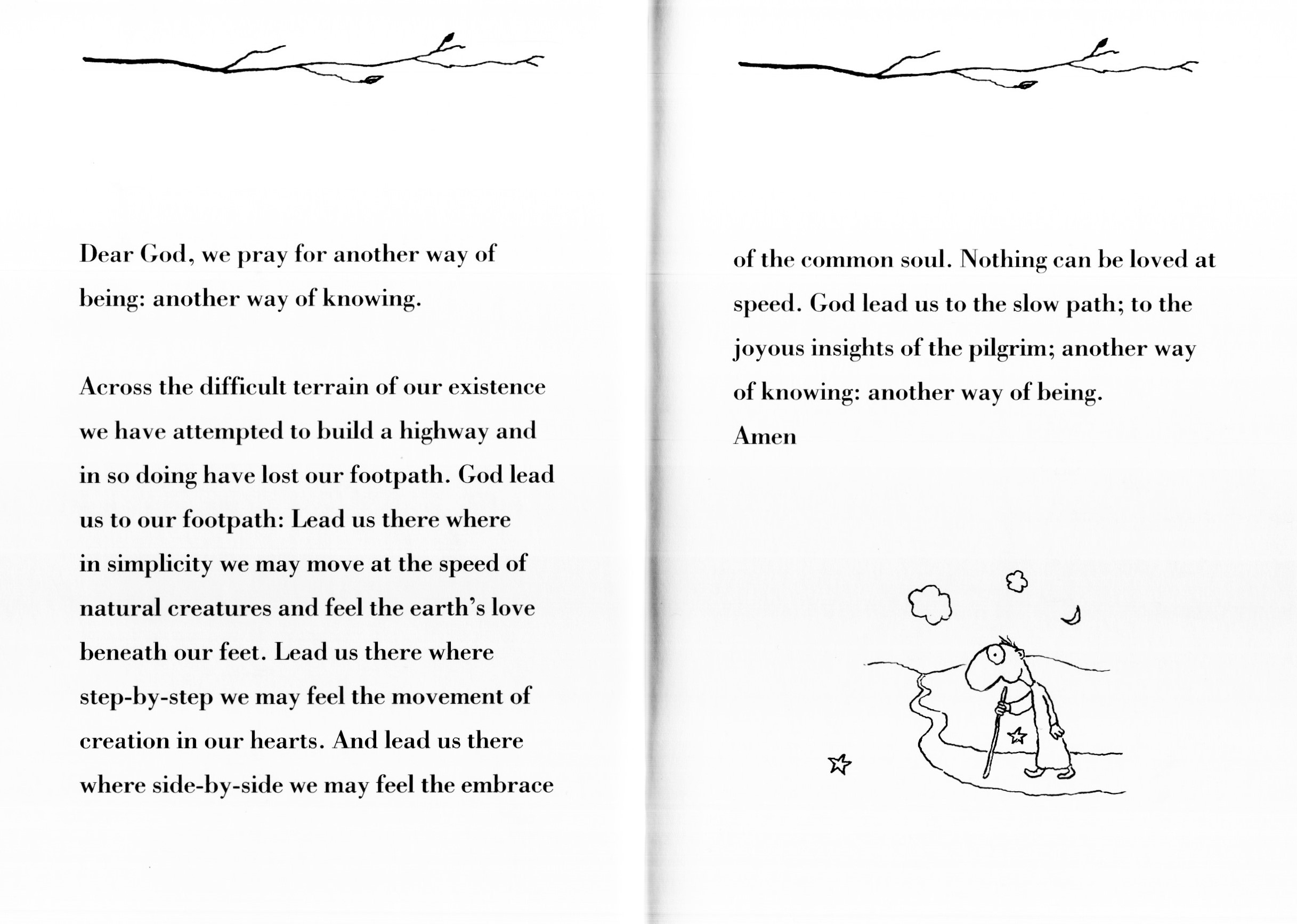

‘Nothing can be loved at speed’ – Leunig

Lucid Dream is the title of my latest composition, 7’52 of flowing orchestral polyphony with an important solo part for cor anglais or alto saxophone. (To hear it, scroll down.)

A lucid dream is one in which you are aware that you are dreaming – in other words, you are conscious and unconscious (asleep) at the same time, a powerful reminder that there are (at the very least) two parts to the human mind.

In most human cultures, through most of human history, dreams have been taken very seriously, seen as a source of wisdom, prophecy, connection with the gods, or (more recently) a source of insight into ourselves and our unconscious motivations. Dreams come from somewhere deep in us, and often tell stories with the resonance of myth, or present to us in symbolic language things we have not previously been conscious of.

Lucid dreaming takes the value of dreams to another level, as it gives the potential to consciously control what happens in dreams, or even to engage in the Buddhist practice of dream yoga, said to be a way of realising the true nature of reality.

I chose Lucid Dream as the title of this piece because it suggests this multi-layered inner complexity of the mind, a sense of deeper undercurrents, of there being meaningful and purposeful goings-on below the level of conscious awareness. And – since the English word ‘lucid’ derives from the Latin for ‘light’ – I also chose this title because for me it has associations of bringing light into dark places.

I completed the composition of Lucid Dream just as news arrived that Australian cartoonist-philosopher Michael Leunig had died. Leunig’s views were sometimes controversial, but the honesty and compassion, the childlike innocence and vulnerability, and the sometimes delightful, sometimes outrageous sense of humour that came through in his work inspired me as well as many other people, and I immediately decided to dedicate Lucid Dream to his memory, adding my favourite line from all of his work as an epigraph: ‘nothing can be loved at speed’ (from a little book called The Prayer Tree – see below).

I had actually chosen the title Lucid Dream before hearing of Leunig’s death, but it seems to me now that ‘lucid dream’ could serve as an apt metaphor for his work, possibly even for his life as a whole. So much of what he drew, wrote and painted obviously bubbled up from his unconscious mind (subconscious) like a dream, became ‘lucid’ (came into consciousness, into the light) then was noted down, as a dream may be, and shared with the world.

As it happens, that is also a good description of my own compositional process: my unconscious mind makes up musical ideas (melodies, rhythmic patterns etc.), just as it does my dreams and all the stories and images they contain. When I’m receptive, these musical ideas come up into consciousness, then, when I’m able to, I make note of them and start to work with them, figuring out their implications, what they’re telling me, and where they’re suggesting I take them. (So the creative process for me is very similar to dream work generally, and to what Jung called ‘active imagination’.)

Lucid Dream has evolved from earlier works with the titles ‘Lucid Dreaming’, ‘Dreaming’ and ‘Of Joy and Sorrow’, but has been completely revised and in a number of places rewritten; effectively it’s a new piece. (I’ve added a brief history of its evolution below for anyone who might be interested.)

Michael Leunig, the dedicatee of Lucid Dream, loved music and was reported to be listening to Bach and Beethoven when he died. There is no way of knowing now if he would have liked this music, but I hope its intuitive flow and its refusal to ‘love at speed’ would at least have met with his approval.

Neil Buckland

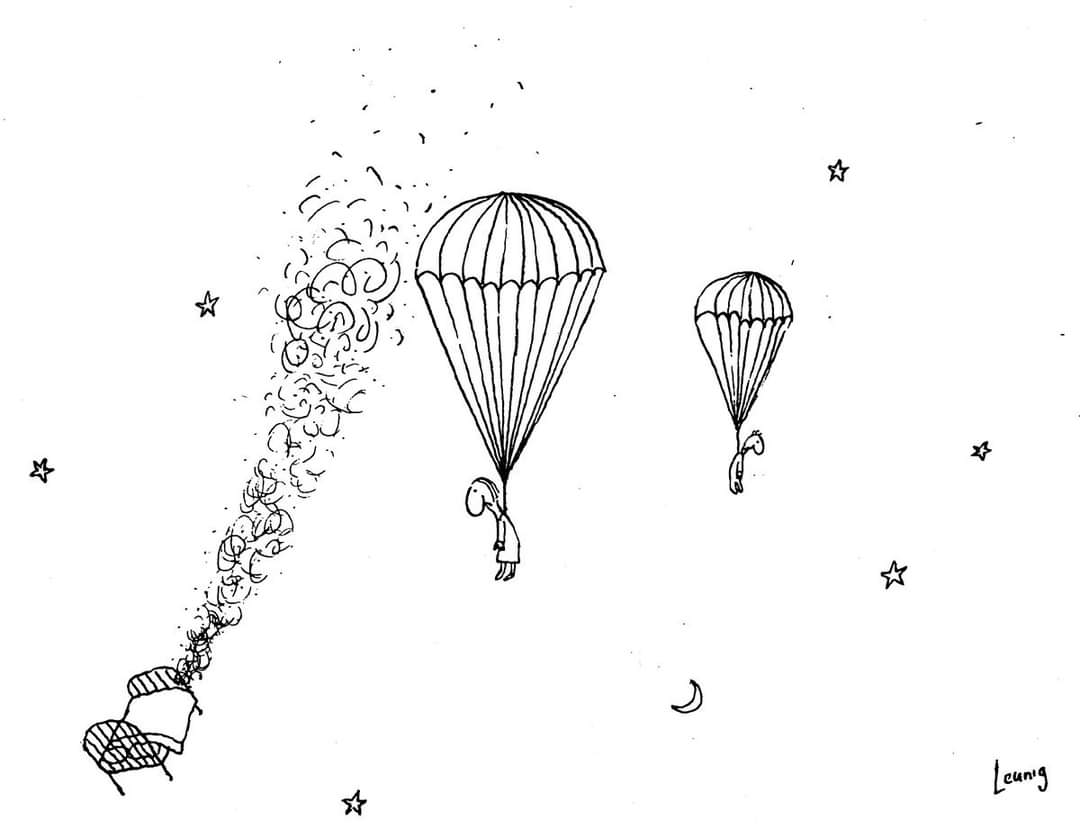

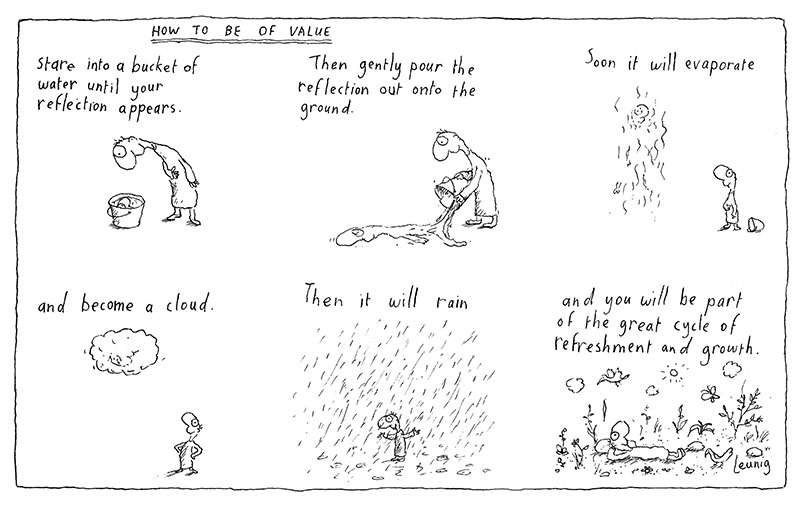

A few samples of Leunig’s work; first, when the dream ends:

The evolution of Lucid Dream

I wrote the first version of what is now Lucid Dream as the slow movement of a Concerto for Didgeridoo and Orchestra that was never completed. In this early form, in B minor, the string and upper woodwind parts (flute, oboe, clarinet) were much as now, but there was nothing corresponding to the current cor anglais/saxophone part, and a didgeridoo provided a constant rhythmic drone bass with occasional interjections of higher, unpitched sounds.

I eventually put the unfinished Didgeridoo Concerto aside, and in 2013 published this original version of Lucid Dream as a separate piece, with the title Lucid Dreaming, then, in 2016, re-published it as the final part of a three-movement piece titled Fuzzy Logic, Lucid Dreaming (with no changes to the music but many more interpretative instructions for the didgeridoo player).

Four years later (2020), I was composing the collection Climates of the Mind for bassoon and orchestra, a suite of pieces representing various states of mind, and it occurred to me that this piece, Lucid Dreaming, could represent dreaming generally but would need adjusting somewhat, so I revisited it, and in the end radically revised it – transformed it, really, eliminating the didgeridoo, adding a completely new melodic part for solo bassoon or cor anglais, and transposing the whole thing down to G# minor. This version was published under the title Dreaming, in two versions, one shorter, one longer.

Then, in 2023, composing Songs of Joy and Sorrow on texts by Kahlil Gibran, I realised that the shorter version of that new piece, Dreaming, could serve as the basis of a song, though a good deal of adapting and adjusting would be necessary. So I again rewrote the music, transposing it back up a semitone to A minor and using the solo part for bassoon or cor anglais as the basis of the soprano’s vocal part, a setting of the text ‘Of Joy and Sorrow’. Numerous changes and additions needed to be made to suit the lyrics, so in effect this became a completely different composition. And an even more radical rewrite ensued when I decided to make a chamber music version of the song (originally for soprano with orchestral accompaniment) and composed a completely new piano part – which I then added back into the orchestral version as an optional part for harp.

Now I’ve again rewritten the music (definitely for the final time!), adding many ideas learnt from Of Joy and Sorrow as well as many new ideas, and transforming the much simpler solo part in Dreaming into a much more extensive, lyrical and expressive form. I’ve transposed the whole thing down to G minor, where it better suits the range of the solo cor anglais or alto saxophone, and completely revised and in a number of places rewritten the other parts. Effectively this is a new piece and so it has a new title (though obviously related to those of its ancestors), Lucid Dream.

Neil Buckland

Leave A Comment